#RPGaDay2020 Day 16 - "Dramatic"

As I've said many times, even this month, RPGs are all about good storytelling. And as a GM it's easy to have that story be interesting, exciting and rewarding. If the players like the story, then by definition, it's interesting. If there are unknown outcomes, especially if you can pull off a knife's edge situation, it's exciting. And of course, if the players advance, get cool new stuff, etc. it's rewarding.

But there are other goals with different types of stories that are harder to accomplish. One of those is "scary" which requires that you understand horror narratives and then be able to translate it into a role playing game where you don't control many of the aspects of it. But today's essay is about "dramatic" and that's also hard to accomplish for a variety of reasons.

In fact, I've had some experiences where I utterly failed to make things dramatic when that was what I was going for. I've introduced important NPC's to the party, and because they didn't understand the scope of who they were meeting, it totally fell flat. I've had major world events occur, and again, because they didn't understand the world building, it was just a narrative detail. I've realized that real people in the game world might have been impressed by these changes, but players in a game only know what they've experienced at the table, and maybe what they read in that guide or handout that you created. To make things dramatic, the events need to apply to them--and here are some techniques I've created for accomplishing that.

Empathy

First and most important, for something to be dramatic, the players need to care about what is going on--not the characters. They need to care about the NPCs or the things their characters hold dear, or the groups that they are a part of, or the city/country/world. It doesn't matter how much the characters care--if the players don't care then any changes or threats to those things will fall flat.

My most recent campaign has been much more of a sandbox, and the players are starting to develop the things they really care about, and the story keeps going towards those things. I always have story elements and next steps ready, but I keep the plot open, and only bring in those other things when the story begins to slow down.

By doing so, we start getting family connections that are important, hangouts that the party like to use, because the players are starting to be invested in it and storylines that characters have chosen to pursue. Each of these is a great basis for making the story dramatic, by either including or threatening these things.

Relatable

This is the next step past empathy. The story has to be going in a direction that both the characters and players can understand. If the big local hires them to "stop this great demon from being summoned by the bad guys" that might be exciting; it might be a great job; it might offer them opportunities for experience and wealth, but it won't be dramatic unless they can relate to either who is summoning the demon, why the demon is being summoned and what that actually means--ideally all three.

In a video game, the NPC quest giver often says "Quickly, get to the next NPC, or this bad chain of events will happen." If your inventory is almost full, or you need to practice or do administrative work, but still rush off to the next NPC, then that game has capctured the dramatic element. You have chosen to advance the story, rather than deal with your own agenda--even knowing that the next NPC and timeline will still be unchanged by the time you get over there.

Opportunity

This is related to relatable. Once the party relates to the event or quest or situation, they have to have some ability to affect the outcome. The "and then your beloved brother is found dead in his room" is certainly a major story element, but it's very risky in terms of drama. If your own real-life brother was found murdered in a room, that would certainly be dramatic...but an RPG only exists for 4 hours a week (or whatever) and so such an abrupt event seems mean and created to drive a plot--which it is. Instead, there needs to be an opportunity for the players to change the outcome, successfully or unsuccessfully.

If, instead, the brother says that he got into a bad situation with bad people. The party can rush around and try to figure out who, why and how to fix the situation. If they make enough progress, maybe they can get it resolved. Maybe they have to make a devil's bargain to bring a debt onto themselves. Maybe they spend too long, and the brother's hunters find him. Those situations are all dramatic, because the party had an opportunity to affect the outcome, and regardless of what happens, they are more invested in both the path AND the outcome.

Consequences

Finally, the story needs to have consequences and this is much more subtle than it sounds. Sure, if the brother above gets killed, that's a consequence...but so is the devil's bargain. And even if they succeed, there should be consequences. They don't have to be terrible or even bad, but there has to be something that marks the occasion in the player's mind. Maybe it's their brother's death, maybe it's having a big favor out there for an unsavory type. But maybe it's as simple as knowing that the brother is a screw-up and gets involved with bad people, and is likely to again.

Even in the best case, where the brother was innocent and was just in the wrong place at the wrong time and the situation is resolved amicably with nobody getting hurt--there is probably still a consequence. A big-bad notices the player as a power in the area, the bad organization, found has to go underground where they are harder to find next time, or maybe it's as simple as the party knowing that the brother, and all their brothers are going to be more at risk as they become more prominent int he community.

Not all stories need to be dramatic, and not all stories even have to be memorable. But especially for groups that have been playing for a long time, and/or playing together for a long time, it's essential that they feel that there is something notable and different today than all the other times they've played, and a dramatic story is one of the best tools to achieving that.

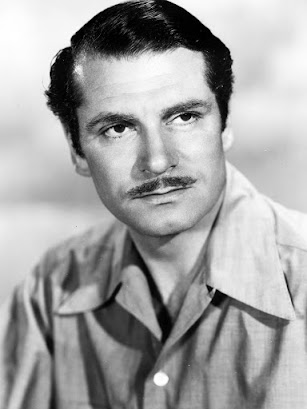

Today's Art

This is Sir Lawrence Olivia, widely regarded as one of the greatest dramatic actors of the 20th century. I chose him as today's picture, for his dramatic reputation, but also because he tended to force his view of drama on to the audience, which sometimes worked and sometimes left him compared unfavorably to his peers. But he had a vision, and worked with others to secure it, and ultimately left a catalog of stories he could be proud of.

Comments

Post a Comment